Those who preserve also serve. That was the message AIA Arizona gave this year in handing out two of its Awards of Distinction not to architects, but to people who made sure architecture survived. These recipients are Zach Rawling and Alexander Malatesta, who together are responsible for the fact that Frank Lloyd Wright's David and Gladys Wright House in Phoenix is still standing and may, depending on how current discussions among various parties proceed, be open for public enjoyment in the near future.

The David and Gladys Wright House is a strange structure. Wright designed it in 1952 for one of his sons, who was a concrete block representative in Arcadia, a tony suburb in the shadow of Camelback Mountain. It belongs to that late period when everything the by then-aged architect did seemed to consist of circles and spirals, and it is both as exhilarating and as problematic in relation to both its interiors and its surroundings as most of those curving structures.

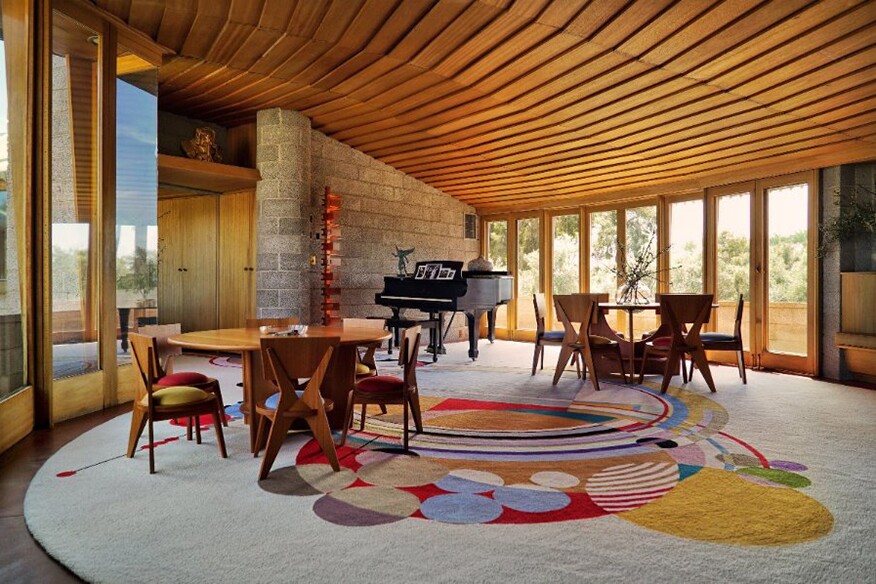

Rising out of what was once an orange grove, the Wright House starts as a ramp curving over the parking area and past a swimming pool into a succession of living spaces that afford sweeping and changing views of mountains, mesas, and flat expanses of the Valley of the Sun. Built out of concrete block and furnished in wood that fits into the complexities of the geometry, the David and Gladys Wright House spirals out of its flat terrain.

We almost lost it. Two men started the movement to save it, and thousands followed. The AIA Arizona award for Rawling is appropriate and deserved, but the one for Malatesta is the one that intrigues me. Rawling is the Las Vegas developer, originally from Phoenix, who stepped in when a plan by a developer called Meridian to build Tuscan villas on the site meant tearing down the house. He bought the property in 2012, and promised to open it up as an educational facility hosting public events, classes, and performances. He then even acquired adjacent lots so that there would be enough room to have the house serve as the core of an extensive program of activities that would have included classes and performances. NIMBY-oriented neighbors stopped some of the most ambitious parts of his plans, but the house has been preserved and will, one way or the other, be open for public tours.

None of this would have happened without Malatesta (you have to love the fact that he shares his name with the client for one of history’s great unfinished projects, Alberti’s Malatesta Temple in Rimini). The developer who had bought the Wright House to tear it down for cookie-cutter, jammed-together McMansions hired Malatesta, who owns a landscaping service, to demolish the structure. When Malatesta got to the site, something seemed off to him, according to the award citation written by Jones Studio principal Eddie Jones, AIA, based on conversations with Malatesta and Rawling. Though Malatesta is not trained in architecture (he has a high school degree), he recognized that there was a quality about this building that did not merit the ministrations of his bulldozer. He called the City of Phoenix, spoke to whoever answered the phone, and convinced that person to at least to speak to his supervisor. The higher-up agreed that something seemed off, even though there was a proper permit for demolition, and the rest is history—now preserved for all of us to enjoy.

After Malatesta walked away from a job for which he had a contract, forfeiting his pay and potentially damaging his reputation, thousands of concerned citizens stepped forward, but nobody had the means or the commitment to preserve the house. It took Rawling, an architecture lover and now president of the David and Gladys Wright House Foundation, to step forward and buy the property. What Rawling got for his act of preservation was years of litigation by neighbors who apparently would rather see their energy-wasting, one-percent-housing, Tuscan-travesty domiciles cover our planet than share an example of how you can build a home in a way that spirals out of the landscape to open up to its surroundings with the rest of the world.

Rawling is the hero of the story, and we should all be grateful for the considerable investment in money, time, and emotional energy he put into the Gladys and David Wright House. He deserves the award. But so does the man who stopped, looked, thought, and realized that there was something amazing here, something that offered a vision we should cherish and follow. Kudos to AIA Arizona and Jones, the award nominator, for awarding and making an example of Malatesta. I hope the AIA will use this story as an incentive to find ways to make sure that there are many more Malatestas in our future.