Our buildings arise out of our brains, and our brains—and our bodies—spend an average of 87% of their existence in buildings. And yet, we know relatively little about the interaction of the two. How do we conceive of the ideas and cognitively marshal the information necessary to design buildings, and how does our built environment affect the neural activity inside our brains?

In late September, the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture’s (ANFA) biennial conference, held at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) and the Salk Institute, sought to help answer these questions. It’s no simple task. Architects and neuroscientists work at such different scales, with one measuring things in microns and the other in feet and inches, and they have very different sources of financial support: client fees versus National Institute of Health funding. Timeframes, too, can vary significantly: buildings tend to get designed and built far more quickly than, say, the decade of research that UCSD neuroscientist Terry Jernigan and her colleagues at several universities plan for an adolescent brain and cognitive development study.

The two disciplines also face the challenge of not reducing the work of one into the other. Neuroscience can inform—but should not determine—what architects do, given the range of issues that influence the form of buildings. At the same time, the built environment can affect, but should not delimit, the scope of neuroscientific research, given the complexity of forces that comprise human cognition. Both fields deal with amazingly complicated and beautiful structures—buildings and brains—and the nuances of their work should not get lost in their eagerness to collaborate.

That said, the intersection of architecture and neuroscience can tell us a lot about how we perceive, imagine, interpret, and respond to buildings, reinforcing the Winston Churchill quote that architect Steven Holl, FAIA, referred to in his keynote talk: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” How that shaping occurs, in both directions, remains the question.

Wading into the world of neuroscience can seem daunting to architects not trained to read MRI scans or EEG readings. Fortunately, a number of neuroscientists have written accessible books on the subject: Anjan Chatterjee’s The Aesthetic Brain (Oxford University Press, 2015), Eric Kandel’s The Age of Insight (Random House, 2012), G. Gabrielle Starr’s Feeling Beauty (MIT Press, 2013), and Arthur Shimamura’s Experiencing Art (Oxford University Press, 2015). One can’t help but recall the Einstein observation that “you do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother.” At the same time, architects like Holl and Juhani Pallasmaa, Hon. FAIA, have shown how architecture represents “embodied mind,” as Pallasmaa called it in a keynote address he gave at the previous ANFA conference.

The back-to-back talks of Holl and Kandel, a Nobel Prize-winning neuropsychiatrist who, like Holl, is a Columbia University faculty member, demonstrated the evocative power of bringing these two disciplines together. Holl displayed one of his elegant watercolors, in which he depicted the human body as an island in a sea called the environment, with the brain drawn as a structure on the island, and the mind as an area within that structure. He went on to describe his architecture as the interaction of mind and body, pursued by moving from concepts to phenomena across what Einstein called “the unbridgeable gap between thought and feeling.”

Meanwhile, Kandel discussed the rise of artists in early 20th century Vienna whose portraiture paralleled many of the psychological ideas of Freud. While not mentioning architecture per se, Kandel’s talk and his recent books refute the idea of the scientist and novelist C.P. Snow that the arts and the sciences have such different methods that they will always remain “two cultures.”

ANFA itself stands as a refutation of that fatalistic fallacy. Many of the papers at the conference came from research teams that included both architects and neuroscientists, working in both academic and professional settings. And many of the conclusions of this research challenge some of the widely held assumptions of the architectural community.

An aging population in the U.S. makes this research increasingly urgent: one in four people will have cognitive impairment by 2050, for instance. Research focused on improving cognitive health shows that physical activity helps, but so does an “enriched environment” with “novelty, challenge, and engagement,” as architect and cognitive scientist Laura Malinin and her colleagues at Colorado State describe it. Their research suggests that older people benefit from walkable communities rather than the auto-dependent locations where much senior housing has been built; and, contrary to the institutional quality of some of these facilities, seniors require stimulating environments.

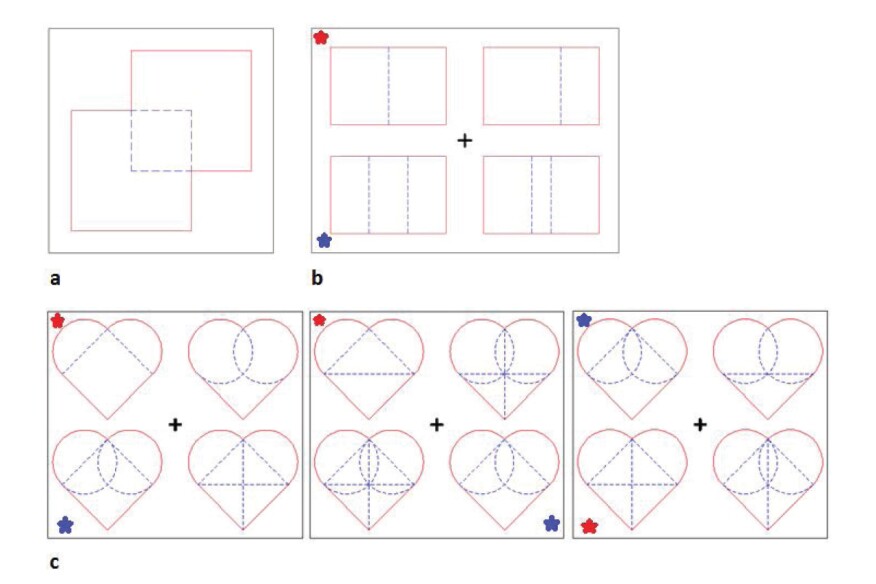

Meanwhile, Indian architect Sudhir Pasala and his colleagues presented research showing that simple, symmetrical, and connected forms help spatial perception, while fractal-like shapes help us navigate within a building or around a city. The takeaway: That an overall orderly environment needs an occasional architectural or urban landmark.

Neuroscientific research also challenges some of our assumptions about the accommodation of people with disabilities. The masters thesis of Betsy Nolen, Assoc. AIA, a recent University of Maryland architecture graduate who now works for Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners, showed how an environment’s acoustical and tactical qualities, designed through careful material and spatial choices, can help people with little or no sight navigate their surroundings. Not only does such design enhance everyone’s experience of a building; it also challenges the visual ways in which we often conceive of buildings.

At the same time, stroke victims, according to architect Michael Chapman and his colleagues at the University of Newcastle, Australia, spend most of their recovery time at home, and so designing residential environments in ways that have proven successful in institutional settings—access to nature, daylight, and color; an organized and easily navigable interior—takes on new importance. And yet recovering stroke victims also require some degree of challenge, to help strengthen physical and mental deficits and weaknesses, and so there should be an easy way to retrofit interiors to meet those needs.

Research on the adolescent brain raises similar questions. We all know that adolescents sometimes engage in risky behavior, but how might we design environments in ways that discourage those risks, or at least make them less dangerous? Motor vehicle accidents remain the leading cause of death among adolescents, for example, and so reducing youths’ dependence upon cars, with more walkable and less auto-centric communities, would mitigate that risk.

Just as architects learned in the 20th century that there exists no universal building that works well everywhere, neuroscience has recognized that, as one researcher put it, “there is no universal brain.” Culture and context matter, and how we think and feel reflect the environments in which we develop. While we still have a rudimentary understand that relationship, as Kandel reminded everyone, the ANFA conference made it clear that we have made real progress, in academic research centers around the world, as well as at architecture firms. In an era in which sensors wrap our bodies and our buildings, we have begun to gather data about the physiological and cognitive effect—good and bad—of every structure. It is indeed mind-boggling.