Is Modernism evil? In the movies it certainly seems to be, at least when it comes to the lairs of master criminals and megalomaniacal would-be world destroyers. Now 15 of those ultimate mancaves (none of the villains are female) have found a home in Lair: Radical Homes and Hideouts of Evil Movie Villains (Tra Publishing, 2019), which presents itself as the black bible of bad architecture. Assembled by Miami-based Chad Oppenheim, FAIA (along with Andrea Gollin), it is an idiosyncratic selection of movie sets and houses from Goldfinger’s base to the war room featured in Dr. Strangelove and up to the Alaskan retreat of Mark Zuckerberg/Steven Jobs persona Nathan Bateman in the 2014 film Ex Machina. Plans and sections, as well as interviews with some of the set designers and architects involved, give us insight into these dark dungeons of evil and madness.

Oppenheim’s selection emphasizes a particular kind of lair. Most of them show up in action movies, especially James Bond films or movies that follow that model. Caves and underground spaces, far removed from light and enlightenment, predominate. All but one of them (Lex Luxor’s version of Grand Central Station in New York, located 200 feet below the real one, in the 1978 version of Superman) are indeed dominated by clean lines, abstraction, and what the author calls “a kind of Mad Men aesthetic.” That means that the look resembles the sort of Modernism popular among businesspeople and their families during the 1960s, even if some of the movies, like Ex Machina and the Tony Blair-inspired political thriller Ghost Writer, look back at this period rather than taking place in them.

Sean Connery and costars in "Diamonds Are Forever," filmed in John Lautner's Elrod House in Palm Springs, Calif.

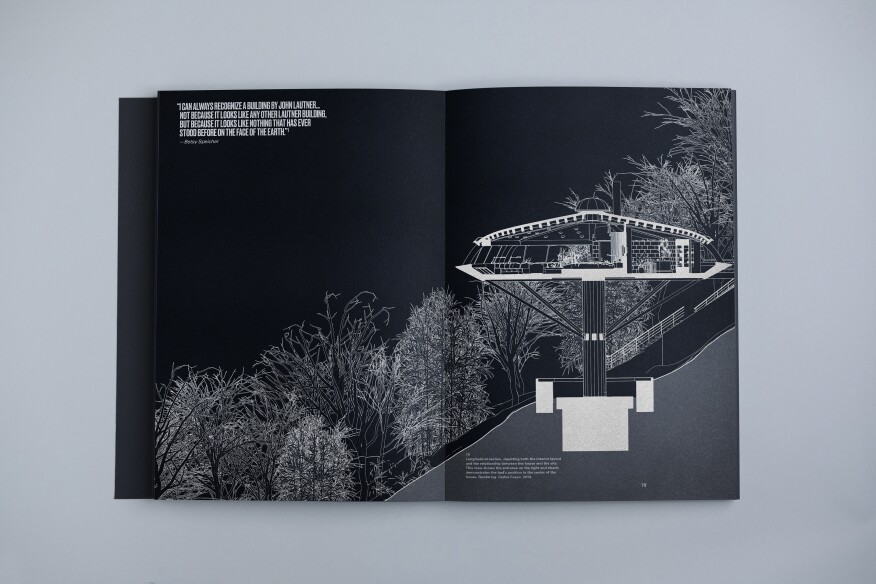

What is also remarkable is that almost all of them feature curves, domes, and circular spaces. Some of that has to do with the logic of film sets, which try to visually unify environments even though they might exist only as fragments that have to accommodate all the close ups, pans, and cuts that help create a scene. Part of the reason for the circle fad comes from the fact so many of the sites are supposed to be caves, such as Scaramanga’s home and launch pad in The Man with the Golden Gun, which is situated under a volcanic crater lake in Japan (no lakes were harmed in the making of the movie; like almost all the sets, it was a, well, a set). Yet when directors chose houses, they also had a tendency to opt for more or less circular ones, such as John Lautner’s Chemosphere (in Body Double) and Elrod (in Diamonds Are Forever) Houses, or ones with curved roofs, such as Lautner’s Garcia House (Lethal Weapon 2). Oppenheim speculates that the fact that these are often “gladiator ring[s]” in which adversary square off might also be a reason for the recurrence of the shape. Yet there seems to be something more basic at work here. Even Luthor's Superman hideout features a round foyer and an apsidal room festooned with palms. Grand ambitions mean sweeping spaces, and defying gravity or the norms of construction is part and part parcel of being bad.

The ultimate curve, of course, is Star Wars IV’s Death Star, a universe containing Piranesian depths, endlessly curving corridors that enhance the sense that you are caught in a maze, and an exterior whose ribs and pockmarks are so deep that they become canyons through which starfighters can zoom. Here evil rises to the scale of creating a complete other world, one in which the dark version of reality (though the Death Star and its most famous denizens, the Star Troopers, are, contrary to the White Knight/Black Knight convention, white-clad) is total.

It is a particular kind of evil men that occupies these lairs. They are would-be dictators and control freaks who do not like people or the current reality. They dream of a post-human future that will be dominated by technology. It makes you remember that real dictators, from Hitler to Stalin to Ceausescu and all the way to Xi, usually prefer Classicism of some sort. Petty criminals and serial killers are at home in the neo-Gothic (at least according to films). Modernism is the preferred style of the Goldfingers of this world. What is also interesting, which Oppenheim does not mention, is that most of their adversaries, including in particular James Bond, are also Modernists who like the martinis dry and their bedrooms clean-lined.

So, what are we to make of these spaces? “Scaramanga’s lair,” says Oppenheim in his foreword, referring to the Man with the Golden Gun’s place of evil, “has inspired me in my work as an architect.” That is an either brave or a foolhardy statement for an architect to make, even if his clients have included master action-movie director Michael Mann. Perhaps the classicists are right and even domestic Modernism of the benign sort has its roots in a particular brand of bad?

I think not. What Oppenheim points out is that movies shape our sense of what is possible in architecture as much as the canon, and that bad guys not only often get the best lines, they also get the best lairs. That, in turn, is because evil in movies—as opposed to real life—is easy to recognize. In the interviews Oppenheim includes in the book, designers talk about making their antiheroes’ traits visible in space. The heroes just are—mirroring all of our less-grand lives. The message these movies convey is that we are basically good and we live in a normal, recognizable reality. Evil is a bad place in both a literal and a metaphorical sense—out there and beyond redemption in style, place, and ethics.

The most beautiful and most slippery of all the lairs Oppenheim features is not at all round and is largely without the clean lines through which men with guns dash in the other films. It is the Vandamm House, a set designed for Hitchcock’s North by Northwest by Robert F. Boyle when Frank Lloyd Wright proved too expensive. Cantilevered off the face of Mt. Rushmore, the house is a slightly clumsy, but still exhilarating version of Fallingwater, its stone-clad vertical masses running up past overhanging eaves and gridded expanses of glass. Inside, levels change, and furniture nestles into nooks. This is an altogether more comfortable version of Modernism, one in which you can imagine living. That might be the point: the villain here is upper class, but not megalomaniacal. He is just a spy who sells information. The evil you inhabit is much less insidious and closer to the good than the one that is beyond the pale or over the sea in a South Sea island.

Aaron Betsky is a regularly featured columnist whose views and conclusions are not necessarily those of ARCHITECT magazine nor of the American Institute of Architects.