This is the author’s first post in a five-part series covering six Autodesk workshops that explored the relationship between emergent digital collaboration technologies and the challenges in project delivery.

Despite all the digital design, analysis, and communication tools at our disposal, the AECO (architecture, engineering, construction, and operations) sectors have yet to improve significantly. How can technological, procedural, and cultural transformation combine to make the building process better?

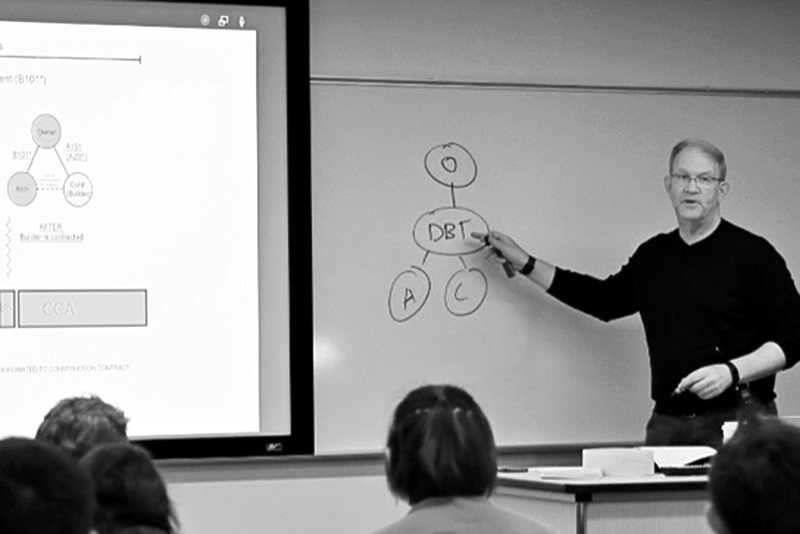

Sean Airhart/NBBJ

Phil Bernstein

Over the past 18 months, Autodesk (where I was previously a vice president and am now a consulting fellow) sponsored a series of six workshops around the globe to explore the relationship between emergent digital collaboration technologies and the challenges of improving the delivery of the built environment. With nearly 100 industry professionals—architects, engineers, builders, and owners—in attendance across the sessions, these day-long conversations explored the opportunities and challenges presented by fundamentally changing the way projects are organized and executed via deep process transformation and the disruptive potential of internet-enabled digital collaboration.

Invited by Autodesk to provide my expertise in the nexus of project delivery and new technology, I participated as both observer and provocateur in each of these sessions, which were professionally facilitated to guide—but not influence—the discussions, and learned a tremendous amount about how experienced industry leaders see how the AECO industry actually works.

And while these sessions occurred in places as different as London and Costa Mesa, Calif., the messages and conclusions were surprisingly consistent, derived from a shared sense of frustration about AECO’s unrealized potential and from a real optimism that change was indeed possible.

In a series of five articles over the next several weeks, starting here, I’ll summarize the observations and insights of this collective effort, and outline the most important ideas that arose consistently across the six sessions.

It wasn’t difficult to arrive at the common and well-understood trope about the current state of the industry: Players operate in silos, work is rarely efficient, and the resulting operations are risky—and frequently unprofitable. It was important to get that out of the way early to move ahead to a deeper analysis. At the heart of these albeit well-founded concerns, however, was an obvious characteristic of information and data exchange within the AECO enterprise, which I will call transactional incompatibility. Projects are delivered with a heady mixture of various tools, standards, data types, and formats, none of which are vaguely compatible, and this disaggregation mirrors—and in many ways is worse than—the structure and protocols of the industry itself. Of course, tools from Autodesk play directly into this mix, augmenting the digital capabilities of the industry while adding to the collection of formats and platforms.

An ideal state, however, would be characterized by information that is clear, compatible, transparent, and consistent—in other words, trustable. This is more than a technological problem, however, and was characterized in the past as “the challenge of interoperability”: “If only all the software were just compatible, all industry problems would be resolved!” is a frequent plea. But as discussions among workshop participants made abundantly clear, data incompatibility is a symptom of a larger disease—one that is characterized by technical, procedural, and cultural roadblocks.

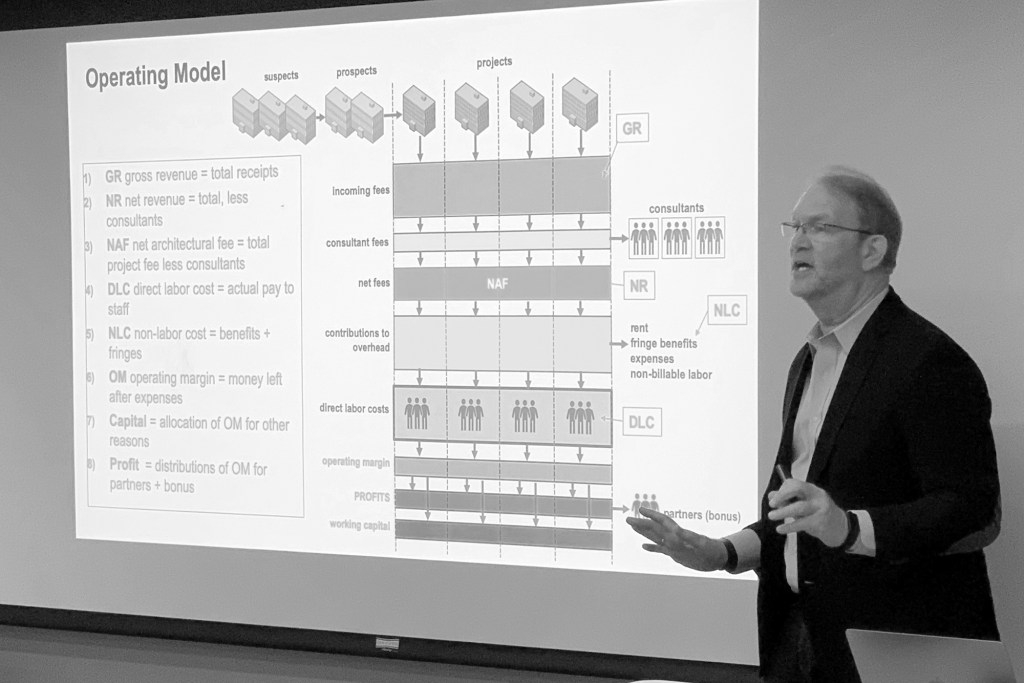

Courtesy Autodesk

Beijing skyline

Technically, the AECO supply chain is just starting to be digitized, an unsurprising observation given that McKinsey Global Institute has characterized construction as one of the technologically slowest moving, least productive industries on the planet. Lacking a broad organizing force or dominant player, a panoply of applications, formats, and exchange protocols has evolved, optimized for individual parts of the supply chain, but by definition suboptimized for collaboration or connection. The technological hurdles, resulting in a data “Tower of Babel,” are significant.

Even if an imagined technological state were completely seamless, industry processes for transparent, trustable interaction are far from the norm. Delivery models are based on mutual suspicion and inequitable distribution of risk, as well as lowest first-cost, commoditized compensation structures. Rewards for doing well are limited, while punishments for failure are manifold. Desires for cooperation—manifest in proper data exchanges—have limited contractual enablers and, when attempted by the brave, have no support from insurance carriers or bonding agents. Teams looking to work closely together have few examples to turn to, and standards adopted by each industry segment often battle each other.

Rewards for doing well are limited, while punishments for failure are manifold.

Perhaps most challenging are the underlying cultural inhibitors to trustable data. Industry professionals are trained in silos, rarely interacting with other disciplines until their first project, and prioritize different objectives for that work. It is an understatement to suggest that architects and contractors in most instances see the world in fundamentally different ways. Rather than combining that insight to mutual benefit and reward, the players bludgeon each other to protect design, schedule, and budget interests. Clients either don’t understand the attendant risk, or they use disproportionate bargaining power to shed that risk onto their project teams. Trust is almost never part of the equation, and these misaligned goals make coherent, integrated process impossible.

The industry must understand, evaluate, and solve the challenges in each of these categories—technical, procedural, and cultural—in order to make real progress, and the answers depend on looking comprehensively across all three.

It was clear from the results of the project delivery workshops that participants understood that information is a vector for trust. It is necessary to align goals, risk objectives, and ultimately the value delivered to projects by removing inhibitors and building strategies that foster that trust. Therefore, information systems that support project delivery must achieve these ends to engender team, firm, project, and industry success.

In the next installment of this series, I will delve more deeply into those industry inhibitors and define how industry experts in the workshops perceive what’s getting in the way of trustable data and coherent, information-based project delivery.

Most of the Autodesk project delivery workshops were facilitated by Lumenance Consulting.

-

Transactional Incompatibility

Kicking off a new series of articles, Phil Bernstein, FAIA, identifies major roadblocks the AECO industry has yet to overcome even with the breadth of technologies available.

-

Inhibitors of Trust

In his second post examining inefficiencies in project delivery, Phil Bernstein details the obstacles to improving workflows in the AECO industry—and there are many.

-

The Roots of Misalignment

In his third post analyzing project delivery, Phil Bernstein discusses its tenuous nature as well as the unrealized potential of BIM.

-

Moving the Building Industry to Alignment

In his fourth post examining the inefficiencies of project delivery in the AECO sector, Phil Bernstein offers ideas for an improved process.

-

The End of the Data Rainbow

In his final post on project delivery in the AECO sector, Phil Bernstein envisions a digitally integrated, transparent process that could operate as efficiently as the internet.