In 1995, Virginia San Fratello and Ronald Rael were alphabetically seated next to each other in an M.Arch. class at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Since then, they’ve gotten married and taught together at Clemson University’s Charles E. Daniel Center for Building Research and Urban Studies in Genoa, Italy. In 2002, they also co-founded the Oakland, Calif.–based atelier Rael San Fratello, a workshop where models are often the finished product and the goal, posted on the firm’s website, is “to disrupt the conventions of architecture by tackling projects not often of interest to architects.” Rael, 42, an associate professor of architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, and San Fratello, 43, an assistant professor at San José University’s Department of Design, don’t have licenses or more than a handful of completed projects between them; instead, they’re guided by a spirit of political activism and an interest in expanding the boundaries of material technology. Here, they discuss the intersection of immigration and design, the limits of architecture, and an experimental approach to 3D printing—which they explore with their materials research arm Emerging Objects—that they hope will revolutionize our environment.

On being a post-9/11 firm: We were living in New York on Sept. 11, 2001, but it wasn’t until a few years later, when we were designing a house in Texas near the U.S.–Mexico border, that we truly realized how the political landscape could affect our work. In 2006, the Secure Fence Act was passed, financing an 800-mile wall along the border. Many of the laborers in the region had crossed the border from Mexico, and 9/11 was the beginning of the end for that. On the design level, the house had a very affordable steel roof, but, because of the war in Iraq, the price of steel had skyrocketed, and this simple structure, designed to be affordable, no longer was. We didn’t think that 9/11 would intersect with a small house in Texas, but it did.

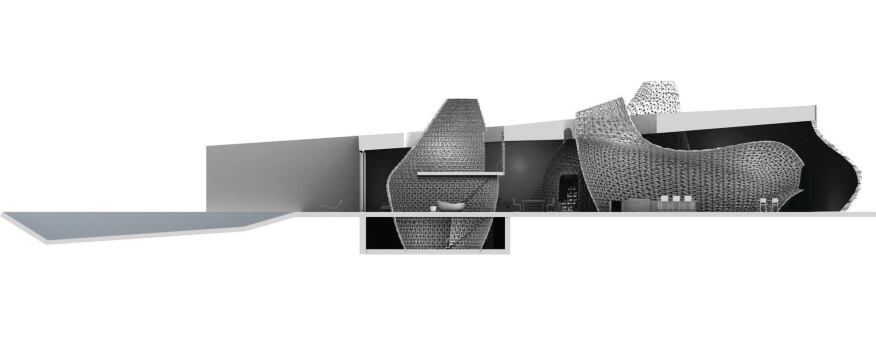

On place and politics: We lived in one of the few apartments in New York’s Chelsea district that opened onto what became the High Line. Before it was the High Line, it was our backyard—we would plant flowers and take walks. When we moved to San Francisco and learned that the Bay Bridge was going to be dismantled, we decided that it should be converted to a park, and entered a sketch in a competition, WPA 2.0, that sought to rethink U.S. infrastructure. We didn’t win, and the Bay Bridge is being demolished, but the project was part of our continuing line of thought.

On 3D printing: We’ve been teaching in architecture schools for 15 years, and have always been exposed to 3D printing and used it in our classes, but we didn’t often use it in our practice because of the expense and lack of durability. Recently, our research on printing with other, more durable materials has taken off. We’ve printed structures out of sawdust, cement, and ceramic. We’ve even attempted using rubber from recycled tires, glass from broken windshields, and salt from the San Francisco Bay. Now we’ve been commissioned by a developer to design houses for a plot north of Beijing that would be among the first 3D-printed houses. The concept typically suggests using one large house-sized printer with a single material. But we see the process as more complex and rich—the walls, for instance, should be a different material from the floor and the ceiling. We want to build a house that does not suggest that architectural traditions should be usurped by new 3D printing technologies.

On theory versus practice: We operate like all architects operate—90 percent of the projects that cross our desks don’t get built. If we based the happiness of our careers on that statistic, we’d be far from happy. Like all designers, we take projects as far as we can, with the hope that a conclusion will present itself in reality. It could be repurposing the Bay Bridge, or bringing awareness to the border wall, or creating a 3D-printed house. The latter project remains conceptual, but we see a trajectory where we could radically change the construction industry. If we don’t get there, we won’t be unhappy. But we’re pushing the idea as far as we can.