The Trenton Bath House, one of the world’s most unassuming architectural monuments, is generally regarded as the birthplace of the aesthetic approach for which Louis Kahn is renowned, in which the dividing line between the ancient and the modern is willfully blurred. Kahn himself acknowledged the significance of the project when, in 1970, he told a New York Times reporter, “If the world discovered me after I designed the Richards [Medical Research] towers building, I discovered myself after designing that little concrete block bathhouse in Trenton.”

I first visited the Bath House, along with a very reverent busload of architectural journalists, after it had been newly renovated in 2010. I spent much of my time that day trying to make my iPhone camera capture the way the sunlight looked as it poured through the open skylight in the center of each of the rudimentary wooden roofs. I described the experience in a blog post: “There are moments when I at least grasp the concept of God. And they always involve a simple building, like Kahn’s Bath House, designed by an architect who understands the ethereal nature of sunlight.”

Two years later, upon reading the obituary for Anne Tyng, who’d worked in Kahn’s office, I discovered that she was in fact the driving force behind my cosmic moment. According to the 1997 book, Louis Kahn to Anne Tyng: The Rome Letters 1953–54 (Rizzoli), Kahn and another architect were working on a “roofless rectangular scheme” for the Bath House but she “almost immediately” came up with a plan involving “four symmetrically arranged squares with hipped roofs.” She wrote that the design was inspired by bathhouses she remembered from her childhood in China, where her parents were missionaries. William Whitaker, the curator and collections manager of the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania School of Design, who became friends with Tyng later in her life, confirmed that the Bath House was largely Tyng’s work. “That’s Anne’s plan,” he told me.

Which is how Tyng, belatedly, posthumously, found her way into my personal architectural pantheon. So I was excited to learn a few months ago that the Philadelphia row house she’d once owned and renovated was on the market. It’s one of those narrow 19th-century houses that lend portions of Philadelphia, like the Fitler Square neighborhood where the house is located, a sweetness that’s rare in American cities. Photos from the real estate listing showed exposed rafters, cunning built-ins, and an impossibly minimalistic staircase: an architect’s house for sure. But the thing that compelled me to visit—that made me fantasize about buying the house, listed for $675,000—was that it’s the one extant solo project by Tyng, who could have been a major midcentury figure, who arguably should have been one, except that she was a woman.

A Reluctant Muse

Gender aside, Tyng was well positioned to succeed. She got her undergraduate degree at Radcliffe College in 1942 and went on to study architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, as part of the school’s first class to admit women. Her teachers included Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Catherine Bauer Wurster, an important advocate for modern affordable housing. After graduating and working for a couple of New York firms, she moved to Philadelphia (where her parents had relocated) and, in 1945, paid a lunchtime visit to a friend who was about to leave her position at Louis Kahn’s first firm, Stonorov & Kahn. Tyng was hired on the spot as her friend’s replacement, and in 1949 she became a licensed architect, the only women accredited by the state of Pennsylvania that year.

Tyng developed an intense partnership with Kahn; she was able to investigate the ideas that interested her—often having to do with the metaphysics of geometry—and nudge them into his projects. She was fascinated with Platonic solids, three-dimensional, multi-sided objects like tetrahedrons and octahedrons, and how we might inhabit such geometric forms. As her daughter, the artist Alexandra Tyng, told me: “She believed that the five Platonic solids were the most basic archetypes upon which all organic structures, micro- and macrocosmic, were formed.”

In the early 1950s, Tyng designed an elementary school for Bucks County, Pa., in which the roof was a space frame with a portion of angular superstructure, an assemblage of triangles, dipping down into the building’s interior. The school was never built, but its central gesture found its way into Kahn’s first major building, the Yale University Art Gallery.

Perhaps the most extreme example of Tyng’s interest in Platonic solids is the Philadelphia City Tower, an outrageously zigzaggy high-rise, a very tall pile of acute angles. “I made the first crude model with triangles in plan on my own time, hoping to interest Lou in developing the idea further,” Tyng wrote in The Rome Letters. Kahn was indeed interested. Though never built, the tower was exhibited in a 1960 Museum of Modern Art show on visionary architecture, and a rendering of it remains in the museum’s collection, credited solely to Kahn. Today, the City Tower looks like an exceptionally prescient take on the future; it could be an early iteration of Norman Foster, Hon. FAIA’s Hearst Headquarters in New York. As Whitaker puts it, she was doing “parametric design by hand.”

The fact that Tyng became pregnant by Kahn—who had been married to his wife, Esther, since 1930, and remained so until his death—and that she’d moved to Rome in 1954 to give birth to Alexandra, and that Kahn later fathered another child, by landscape architect Harriet Pattison: none of this is news. The story was laid out with disarming candor by Harriet’s son, Nathaniel, in the 2003 documentary My Architect. Wendy Lesser’s Kahn biography, You Say To Brick (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017) does add one shocking detail. Upon Tyng’s return from Rome with Alexandra, she found out that Kahn was having an affair with another young female architect on his staff, Marie Kuo.

Nonetheless, Tyng continued working in Kahn’s office for nearly a decade, often designing single-family houses while Kahn was engaged with major projects like the Salk Institute. Tyng has written that she ended their romantic relationship in 1960, and what was left of their professional one came undone a few years later. “Although Lou had plenty of work in the office,” Tyng wrote in The Rome Letters, “he ‘let me go’ by simply not giving me work.” The end came in 1964, during the design of Bryn Mawr college’s Erdman Hall. As Lesser put it, “perhaps the fraying of their personal relationship lay behind some of the problems. … Tyng, with her usual penchant for precise geometry, wanted the bedrooms to be octagonal in shape, nestled together in a kind of molecular design. … Kahn preferred a pattern of interlocking Ts and rectangles.” They’d travel to client meetings with their competing designs and, as Whitaker told me, “One day her model got left in the cab.”

Moshe Safdie, FAIA, was 22 and newly graduated from McGill University when he arrived in Kahn’s office in 1962. He recalls that Tyng’s relationship with Kahn was by then already “getting shaky.” (Given that this was around the time that Harriet Pattison gave birth to Nathaniel Kahn, that is likely an understatement.) Safdie recalls that after a “flare-up,” Tyng disappeared from the office, but he remained friends with her. Together with another architect in the studio, David Rinehart, they worked on an urban design competition for Tel Aviv. Safdie says that Tyng introduced him to Carl Jung’s Man and His Symbols and, more crucially, to D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form, a groundbreaking treatise on the shape of natural objects. “It was a big deal,” Safdie says about his exposure to Thompson. “It’s part of my foundation for thinking about design.”

“I thought the world of her,” Safdie adds. “I think she was major inspiration for Lou. She was certainly a major force.”

A 2011 interview with Tyng

And yet Tyng, after leaving Kahn’s office, never really thrived on her own. Soon after her departure she mounted an ambitious exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania titled “The Divine Proportion in the Platonic Solids.” She also taught at the university, but she never became a tenured professor. And she never managed to find another opportunity to build. Alexandra notes that she was reluctant to dive into the mundane chores of being an architect: “She was always trying to get commissions by entering competitions. … But she did not want the hassle of setting up her own office with employees and running a business herself.”

Perhaps, as Safdie now speculates, she wasn’t anchored enough and was too obsessed with Platonic solids. Yet the drawings and models of Tyng’s unbuilt work reveal a skillful, canny architect. A 1950 submission to a National Association of Home Builders competition cleverly conceals an unconventional hexagonal house behind a disarmingly normal, rectilinear carport.

In the 1970s, she sketched out a detailed concept for Manhattan Landing, an 88-acre development in New York that then-Mayor John Lindsay hoped to see erected on platforms over the East River. Tyng’s drawings, perhaps intended as a rebuke to the corporate Modernism of the official design, depict dense cubist clusters of housing arrayed on a beautifully thought out site plan. Arguably, it is no less anchored than Safdie’s unbuilt Habitat project for the same stretch of river.

Tyng’s misfortune was to come of age at a time when there was very little room for women—particularly sole practitioners—in the architectural profession. Kahn’s office may have been a minefield for the women who worked there, but it was also a place where their design skills were taken seriously. Given that Tyng is remembered primarily for her creative influence on Kahn, it’s not surprising that she developed an aversion to the word “muse.” In The Rome Letters she wrote, “The muse is a shadow figure, an empty vessel only existing to gestate and bring forth visible form identified as the man’s creation.”

In a 1988 essay called “From Muse to Heroine: Toward a Visible Creative Identity,” she struck a more optimistic note, which also serves as a kind of appraisal of her own career. “In the future more women architects will make the difficult leap from [the] conditioned introverted role,” she wrote, “to the challenge of being articulate and visible.”

“Like the Bath House but for Sleeping”

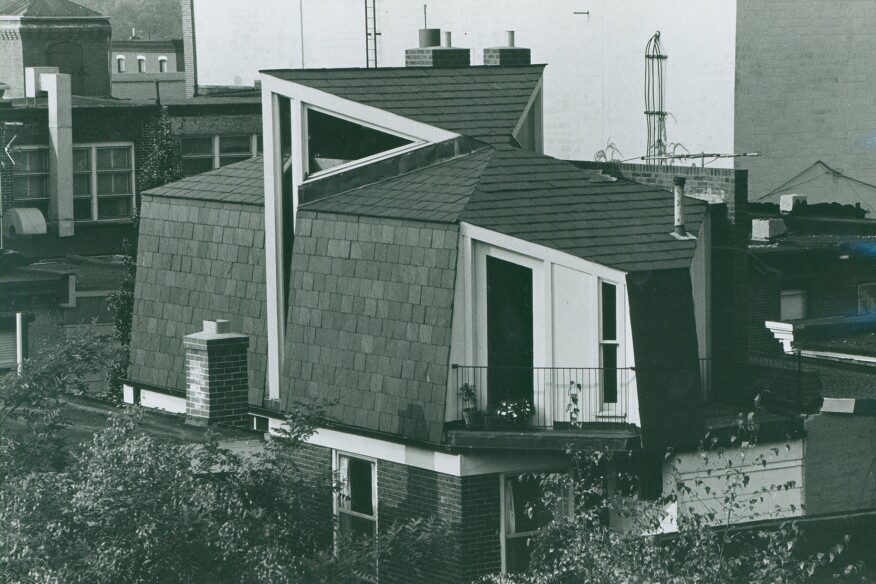

Today, the most powerful expression of Tyng’s architectural vision remains her own house, which she renovated and added to over the course of the 1960s. Tyng’s papers in the architectural archives at the University of Pennsylvania include brochures for all the small-scale gadgets with which she equipped her kitchen: a little electric broiler and a fold-down electric cooktop (designed, according to Whitaker, for Levittown). The house was just 1,320 square feet, and the idea was to limit the space taken up by kitchen appliances. (Curator Ingrid Schaffner, who bought the property in 2005 and owned it for a decade, installed a normal-sized Viking range and added counter space.) The archives also contain astonishing engineering drawings for Tyng’s third-floor addition, a wooden space frame (much like one she designed for her parents’ country house in the early 1950s) resembling a diagram for some advanced form of origami.

When I visited, I walked from 30th Street Station and arrived early. I bumped into a woman, one of the current owners, who was leaving the house with her German shepherd puppy. She told me that living in the house felt like “walking in music.”

After the real estate agent arrived and let me in, I explored the kitchen with its gigantic round, shallow sink inset with smaller basins, and noted how Tyng had shoehorned wee closets into every available nook. But it was the third-floor addition that astonished me. “Like the Trenton Bath House but for sleeping,” is what I wrote in my notebook. From the outside it looks like a clunky mansard roof, but inside, the addition is a work of sculpture, obsessively crafted, with views and living spaces framed by acute angles. Like the Bath House, it was all about naked rafters and sunlight.

Later that day, I visited Philadelphia’s Fabric Workshop and Museum, which was hosting an exhibition, “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture.” It was a dense, meticulous survey of the architect’s work, with the occasional cameo appearance by Tyng. On one gallery wall, the curators illustrate how her early space-frame renderings for her theoretical Bucks County elementary school migrated to Kahn’s sketches of the Yale University Art Gallery ceiling. On a different wall, the exhibition copy asserted that the art gallery has “a triangular reinforced concrete ceiling inspired by Richard Buckminster Fuller’s space frames.” Mysteriously, from one side of the gallery to the other, Tyng had simply vanished from the equation.

Soon after my visit, Tyng’s house also vanished, at least from (semi-)public view. It sold in December for $625,000. The new owner, Dyani Halpern, a 31-year-old cosmetics executive from Pasadena, Calif., initially knew nothing about Tyng. All she knew was how the house made her feel: “I walked in and I started to cry.” Halpern had no idea that this represented one woman’s vision of how we might “inhabit geometry,” or that it has a lifetime of radical architectural thinking tightly packed into its 1,300 square feet. She was simply responding to what she sensed: a “powerful woman energy.” But she’s since done her homework. “I feel like I’ve taken on this responsibility to maintain it and preserve it.” Which is a very good thing, because Tyng’s house is irreplaceable. For an architect who never had the opportunity to create one on a grander scale, it is her magnum opus.