Overcome by Jørn Utzon’s design for the Sydney Opera House, Louis Kahn once remarked, “The sun did not know how beautiful its light was until it was reflected off this building.” Forty years after its opening, one of the world’s most recognizable works of architecture is undergoing a gentle transformation—an incremental remodeling—that is bringing the public icon closer in alignment to its creator’s original vision.

Day or night, the atmosphere in the Opera House is animated by the energy exuded by the throngs of visitors. The nonstop activity, combined with the ongoing renovations, make the Sydney Opera House seem like a living being rather than a static monument.

The story behind the building’s design exemplifies both the best and worst of architectural commissions. Utzon was a mere 38 years old when he won the international design competition for the project in 1956. His proposal for a collection of soaring, wing-shaped shells on the Sydney Harbor promontory captured the imaginations of the jury, inspiring juror Eero Saarinen to call the entry “a work of genius.” Utzon relocated his family to Sydney and set up an office in a boathouse north of the city. For the next decade, the project would consume the relatively inexperienced Danish architect, a man who had become a celebrity overnight.

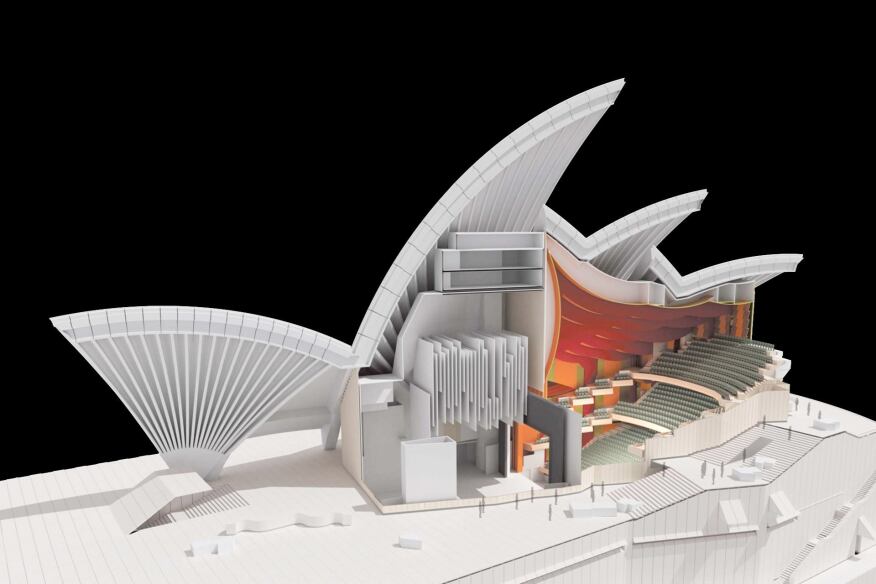

Constructing the ambitious and unprecedented design proved to be a formidable challenge, stymying some of the industry’s most talented minds, including that of structural engineer Ove Arup. Finding a pragmatic and economical way to build formwork for the massive concrete roof shells was one of the biggest obstacles; Utzon’s first design iteration had no repeating elements. Insistent that the wings remain, Utzon revised the roof shells to conform to the geometry of a sphere, which then enabled workers to use a modular set of formwork.

Though the Opera House vaulted Utzon’s career, it also led to its precipitous decline. An ill-fated decision by the client, New South Wales premier Joe Cahill, to kick off construction before key design elements had been finalized led to a dramatic escalation in project costs. When Cahill died suddenly in 1959, he was replaced by Davis Hughes, a fiscally conservative politician determined to squelch what he perceived to be an unmitigated spending spree. He stopped paying Utzon in 1966, when construction was well underway but the interiors were incomplete. As a result, Utzon had to close his practice and return to Denmark. He never set foot in Sydney or his beloved Opera House again.

The local designers hired to complete the project reconfigured the interior significantly from Utzon’s plans. The program for the two—which became three—main performance halls was revised, making the largest hall exclusively for concerts. Opera was relegated to the second hall, pushing drama performances to the podium—which was originally supposed to accommodate only back-of-house activities. In addition to major program shifts, Utzon’s curvaceous geometry was replaced with Brutalist boxes, and materials utilized in these spaces resulted in major acoustical and aesthetic problems that have plagued the Opera House ever since.

Despite the significant interior design blunders, the Opera House became a wildly popular venue. Today, the building attracts more than 8 million visitors each year and contributes more than $1 billion to Australia’s economy. Just try imagining Sydney—or Australia—without it.

Yet buildings need regular maintenance, and the Opera House is no exception. In 1998, the chairman of the Sydney Opera House Trust, Joseph Skrzynski, complained that the building upkeep and incremental modifications were haphazard and sought to rehire Utzon for his expert guidance. In 1999, at the age of 80, Utzon reluctantly agreed to re-engage in the project, enlisting his son, architect Jan Utzon, as a collaborator.

The father-and-son team led several significant refurbishment efforts that, although they don’t undo the existing interior design, apply the elder Utzon’s conceptual approach to the building in a pragmatic way. In a multipurpose reception hall, for example, the Utzons added timber flooring and paneling, ceiling treatments, and a tapestry designed by Jørn for both decoration and acoustical dampening. It’s now called the Utzon Room.

To remedy a windowless foyer on the western edge of the plinth, the architects created a loggia with punched openings that provide a visual connection to Sydney Harbor. Inspired by both the stepped temples of the Yucatán and Denmark’s Kronborg Castle, the apertures occur within deep recesses to preserve the visual weight of the base while providing much-needed daylight and views.

Before his death in 2008, Utzon and his son had developed a set of design principles that continue to guide the ongoing renovations. One long-awaited project is the interior remodel of the opera theater, which will expand the orchestra pit, improve acoustics, and enhance air circulation. Another is an underground service tunnel for trucks and other heavy vehicles—an ambitious undertaking aimed to solve the current problem of conflicting pedestrian and vehicular traffic.

It may seem counterintuitive that architectural icons can become better buildings over time. When I expressed this to Jan Utzon during one of our email exchanges, he said that a working and living center for the performing arts such as the Sydney Opera House requires the ongoing accommodation of new ideas and approaches to performance, in addition to basic technical upkeep. He also shared this story:

“My father and I once passed through the great cathedral of Palma in Majorca and were admiring the architecture and all the arrangements in the church. My father asked one of the custodians about when building works commenced. The response was about 1150. My father then asked when it was completed, and the custodian responded, ‘Complete? It is not complete yet.’ They were still working on the building.”

Like other historic, actively used monuments—Jan Utzon suggested the examples of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City or La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona—the Sydney Opera House is in a continual state of becoming. This seems only appropriate for the architect who famously described architecture as being “on the edge of the possible.” After 40 years, the Sydney Opera House is not only recalibrating itself to fit modern times, but it is also reconciling itself with its unfulfilled conceptual origins.

In a 1965 article, Jørn Utzon conveyed his aspirations for the visitor’s experience of the Opera House. His description captures the spirit of the building’s evolution today. “You never finish with it while you move around it or see it against the sky,” he said. “This interplay with the sun, the light, the clouds is so important that it makes the building into a living thing.”

Read Blaine Brownell's full interview with Jan Utzon, and learn more about the epic rise and tragic tale of Jørn Utzon here.