Talk about green building—and the third-party standards and certifications associated with it—typically centers on the project site, envelope, systems, and interior finishes. Less a part of those conversations, on paper at least, is occupant wellness. A new standard aims to change that.

The Well Building Standard is a project of the International Well Building Institute (IWBI), which itself is the brainchild of eco-branded real estate developer Delos and is organized as a for-profit social enterprise. The performance-based standard was released to the public on Oct. 20 during the institute’s inaugural conference in New Orleans. Its goal is to facilitate human health through seven thematic categories—air, comfort, fitness, light, mind, nourishment, and water—with requirements meant to align with those of LEED. Like LEED, the Well Building Standard will be administered by the Green Building Certification Institute (GBCI).

“Sustainability and health and wellness go hand-in-hand,” says Michelle Moore, senior vice president at the IWBI. “It was very important to us to be collaborative and complementary and build on that [LEED] platform as opposed to creating redundancy or … additional paperwork, additional time—things that wouldn’t be value-added.”

The standard, which is intended for new and existing commercial, institutional, and multifamily projects and tenant spaces, was formally reviewed by a group of physicians, researchers, and practitioners in an effort to qualify its wellness claims and proposed architectural solutions. It is also overseen by an advisory council that includes Jason McLennan, CEO of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), Mahesh Ramanujam, chief operating officer of the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) and president of GBCI, and Whitney Austin Gray, health research and innovation director at Cannon Design. It even got the nod from former president Bill Clinton as part of the 2012 Clinton Global Initiative.

“This is the start of a powerful new movement,” McLennan said in his opening remarks to the more than 450 Well conference attendees last week. “The question for today is: How can buildings support our living systems at the deepest level possible?” USGBC CEO Rick Fedrizzi also addressed the audience, calling the new certification “a standard that seemed to make a lot of sense.”

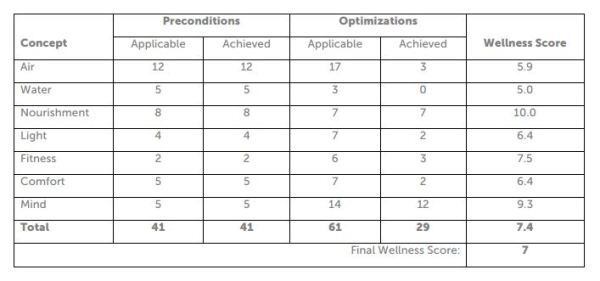

Well is now finishing a two-year pilot on several projects, which total more than 7.7 million square feet of space and include the William Jefferson Clinton Children’s Center in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, CBRE’s global headquarters in Los Angeles, and the Phipps Center for Sustainable Landscapes in Pittsburgh. Well-certified projects are scored based on their ability to meet the full set of conditions prescribed for each of the seven impact categories with the opportunity to improve their scores by fulfilling additional optimizations. The Silver, Gold, and Platinum designations are renewable on a three-year basis and, as with LEED, are marked with a plaque.

The list of more than 100 conditions and optimizations across the seven categories include: air filtration and filtration maintenance; asbestos abatement; limits on the amount of certain inorganic contaminants present in drinking water; a ban on the on-site sale or distribution of foods containing partially hydrogenated oil; a balance of ambient illumination and tasklighting, when necessary, at workstations; workplace incentives that promote physical activity; adjustable workstation desk and seat heights; and the availability of health and wellness literature throughout the building.

The IWBI also plans to launch a Well Accredited Professional (AP) credential next spring. “[W]e want to make sure the Well AP program is working in alignment with other professional credentialing programs in the industry,” Moore says. “We don’t want to duplicate. We want to add value, add knowledge.” The institute also plans to publish supplemental, research-based texts, called Wellographies, for each of the standard’s impact categories beginning early next year. Additionally, as a for-profit social enterprise, or B-corp, the IWBI will reinvest 51 percent of the net-profits from Well into the built environment.

Health and wellness, Moore says, are “a very powerful expansion of the ideas that the building industry can carry.” But at a cost of $100 per occupant for implementation in a commercial office building, as Moore estimates, it’s difficult to determine at this early stage whether Well will catch on given that current standards like LEED and Green Globes come with their own costs. Additionally, while the standard applies to multifamily and tenant spaces, designers and building managers can’t guarantee that occupants won’t eventually bring in toxic materials or that occupants will maintain healthy living practices.

Moore likens Well to a new technology. “You have early adopters … who oftentimes pay a premium related to the learning curve,” she says. “They help to forge the marketplace for everybody else. You have a cost curve that tends to be a little bit higher in the beginning and then drops rapidly over time as you get greater adoption and greater proliferation of knowledge.”