Project Details

- Project Name

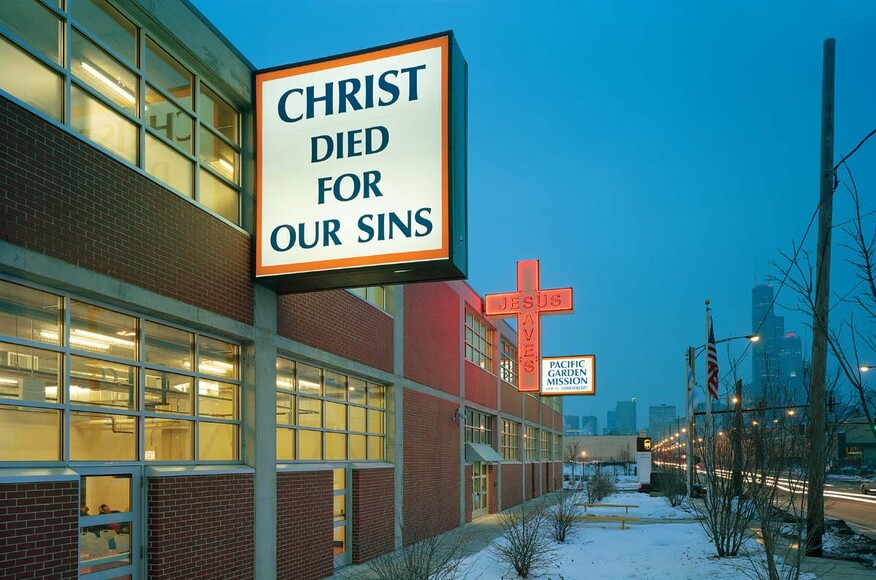

- Pacific Garden Mission

- Location

-

Chicago ,IL ,United States

- Client/Owner

- Pacific Garden Mission

- Project Types

- Other

- Size

- 156,000 sq. feet

- Year Completed

- 2007

- Shared by

- Xululabs

- Consultants

-

Landscape Architect: Peter Lindsay Schaudt,Structural Engineer: The Structural Shop,null: Lehman Design Consultants,Electrical Engineer: Lehman Design Consultants,Plumbing Engineer: Lehman Design Consultants,Civil Engineer: Daniel Creaney Company,General Contractor: Walsh Construction,Schuler Shook,Building Technology Associates,Trimark Marlinn,J.T. Katrakis & Associates

- Project Status

- Built

Project Description

Homelessness is a grim reality of urban life, but one that many city dwellers would prefer to ignore. Yet, despite public opposition to efforts to build a new Chicago home, there's hope to be found in the story of Pacific Garden Mission, a massive homeless shelter that recently moved into new quarters designed by Tigerman McCurry Architects. Founded in Chicago in 1877 by a Midwestern couple who combined a warm bed and hot meal with ministering of the gospel, the organization today bills itself as the largest continuously operating rescue mission in the country, providing food, shelter, clothing, medical care-and spiritual nourishment-to a broad constituency of men, women, and children.

For years, Pacific Garden Mission had been pressured by the city Board of Education to vacate its men's facility on South State Street in the former Skid Row. As the neighborhood gentrified, the site was increasingly eyed for expansion by Jones College Prep, an adjacent public high school. Mission leaders were willing to relocate, but each time they pursued a site for a new shelter, a wave of NIMBYism swelled up from nearby residents. When the Board of Education began to threaten suit, the mission asked Stanley Tigerman to testify on its behalf. (He was referred to the mission by a student at Archeworks, the alternative design school co-founded by Tigerman that links student teams with nonprofit partners to address social needs.) Tigerman agreed to help. And although a suit was never filed, he soon became more than the mission's advocate. He became its architect.

Before then, Tigerman had been vaguely aware of the faith-based mission, best known among Chicagoans for its illuminated cross emblazoned with the words "Jesus Saves." He began to visit the mission frequently, meeting with its director, staff, and residents. He soon learned that the mission ran a second shelter for women and children west of the downtown Loop. And he gained a new appreciation for its treatment of the homeless. "The mission treated these people with great respect and dignity," he explains. "They are not referred to as indigents, but as overnight guests."

What captured Tigerman's imagination was the poignancy of the project the fact that, given a sudden change in circumstance, nearly anyone can become homeless. Working with mission leaders, he set out to help find a new site. Ultimately, the combination of strained neighborhood politics and the mission's desire to build an ambitious multipurpose shelter led to the selection of a parcel south of the Loop at 14th and South Canal streets, surrounded by commuter rail tracks and parking lots for UPS trucks. Says Tigerman: "There is no urban fabric, literally." The site was selected primarily because of its availability, adequate size, and reasonable proximity to the old site a mile away.

Rather than attempt to generate a pedestrian-friendly building in a pedestrian-hostile environment, Tigerman's approach was to create an oasis-not simply a place to lay one's head for the night, but a retreat from the day-to-day struggle for food, shelter, and personal safety. Its ground-floor gathering spaces and upper-level sleeping rooms surround a central cloister, much like a monastery, which provides a quiet space for rest and contemplation.

As he began to design, Tigerman eschewed overt domestic references such as pediments or gabled roofs. Instead, he adopted a formal vocabulary of brick and structural concrete that blends into its light industrial surroundings. "This is not a home. It's an institution," he explains. "You are trying to get people back into society." Inside, his strategy was to create bright, clean, functional space that can serve many purposes. In addition to its ability to accommodate 1,000 people in bunks-and another 400 on severe winter nights-the 156,000-square-foot facility has a dining room that seats more than 600. Working in three shifts, the mission serves 1,800 people per meal. The facility also includes linen and laundry areas, libraries, two gymnasiums, and a barber shop and a beauty salon. Clothing is donated, sorted, cleaned, and distributed in a basement-level space that Tigerman likens to a store-a store handling more than a million articles of clothing each year.

Residents of the facility tend to hear about it by word of mouth, says David McCarrell, the mission's president. By far, the greatest numbers of guests-about 550 men and 125 women and children in total-are transients who come on a night-by-night basis. After checking in, they are led to a large chamber where they hang their clothes for the night (the room is super-heated to kill lice and other vermin). Then they take a shower and receive a sleeping gown. Medical care is available for those who need it; all are given access to the barber shop or beauty salon.

A smaller number of people sign up for the Bible program ministry, which requires a minimum commitment of 60 days and can last up to a year. These individuals become part of the facility's team and are given work assignments in the laundry, library, kitchen, or cleaning group. In addition to their job, they attend daily classes focused on straightening out their lives. After eight months, the emphasis shifts to career development. Those who complete the program "are ready to go out in the workforce and be productive citizens," says McCarrell. "We want to give them the skills to do that." The mission's 600-seat auditorium is the setting for productions of "Unshackled," the dramatic accounts of transformed lives that the mission has broadcast live on radio since 1950. The program's reach is now worldwide, with translations performed in eight languages.

The mission holds three gospel services in the space each day, says David Fuller, director of facilities and systems. Smaller religious services and other small gatherings take place in the chapel, whose translucent glass walls face onto the courtyard.

Weaving the ground-floor spaces together is a broad, L-shaped corridor known to residents and staff as "the yellow brick road." Its outdoor benches, street lights, sidewalk trash receptacles, and street signs were incorporated to engender familiarity, Tigerman notes. The 20-foot-wide circulation space, whose concrete floor is finished with bright yellow epoxy paint, has reinvigorated the mission, says Fuller. "It's a very interactive kind of place?very much like a street," he adds. The glass-enclosed corridor wraps two sides of the courtyard, allowing borrowed light to enter deep into the building.

In addition to providing daily Bible classes, Pacific Garden Mission has a tradition of helping its clients earn high school diplomas and offering life skills programs, such as checking account management, basic English, and computer training. To aid the efforts, Tigerman provided five classrooms and a half-dozen small counseling rooms. Large sleeping rooms are located on second-and third-floor wings for men and in separate second-floor rooms for transient women, long-term female residents, and women with children. The architects designed the space-saving bunks in a way that allows them to be paired side by side, with a metal partition separating the occupants.

Although the mission earned the proceeds from the sale of two older buildings, the new shelter nevertheless had to be inexpensive, says Tigerman. Ducts, conduit, and fire protection systems are exposed. "So it is a gritty look it's about the grit of a city like Chicago." To further reduce costs, Tigerman used an inherently economical construction system: a reinforced concrete frame with a 20-foot structural bay, eight-inch floor slabs, and nominal 2-foot-square columns. By using brick and glass as infill, exposing the concrete frame, he minimized the perimeter surface area.

Sustainable features of the project include a green roof to manage stormwater and to mediate heat gain and heat loss. Unplanted areas of the roof are covered in highly reflective paving. And domestic water for the residents is heated by an array of 100 solar panels that the city donated to the project.

Two greenhouses will be used to generate organic soil and grow consumable goods. This feature also complements the mission's spiritual orientation. "Any time you can plant something, tend it, and wait for it to grow, it is very helpful in the sense of building hope. And many of our guests have lost that hope for tomorrow," Fuller explains.

Because of its commitment to sustainability, the building not only serves the homeless population, but it contributes to the collective good as well. Chicago has firmly established its position as a leader in promoting sustainable building practices. And Mayor Richard M. Daley is a key player in that effort by having ushered in policies that produced more than 3 million square feet of green roofs in three years.

At Pacific Garden Mission, however, the emphasis remains on helping the individual. For 131 years, mission leaders have sought guidance and inspiration in their devotion to God, choosing to stake their claim in the worst parts of town and persevering through difficult circumstances to minister in word and deed. In the rough and tumble Chicago of the 1870s, it was a calling worth answering. And in the modern city where the homeless continue to congregate, it still is.

Toolbox:

Hotboxes

To ensure that the building remains sanitary, the architects designed hotboxes-separate metallined rooms-off one of the men's and one of the women and children's dorms. These rooms sport specialized heaters (connected to and powered through the central heating system) that heat the space to a scorching 180 degrees. The process kills any vermin, be it lice or bacteria, that might be clinging to the clothing, keeping them safe from infestation and disease. When visitors arrive for an overnight stay, they are asked to remove their clothing, take a shower, and change into a mission-issued nightshirt. Their clothes are immediately put into the hotbox and sterilized. The same happens to the bedding after use and to any donated clothing.

Greenhouses and Composting

"It all began with worms," says Tigerman. The greenhouses on the roof of the mission are run by Nance Klehm, a third-generation nursery owner and expert in organic composting and farming. She brought 10,000 worms to start the greenhouse's composting program, and through the addition of table scraps and other waste from the nearly 6,000 daily meals served since the mission's opening in October, the number of worms has swelled to 30,000 in just a few months, with an eventual goal of 3,000,000. The worms create organic compost, which sells for a pretty penny in the Chicago market and ensures the rapid and robust growth of organic lettuce and tomatoes.

The spoils of these gardens will be sold this summer at a farmer's market in the cloister, with the income from both that and compost sales going directly back to fund the mission's programming.

Bunks

The mission's 1,000 beds were custom designed by Tigerman and manufactured by the American Bedding Company out of Tennessee, a company that specializes in institutional contracts. The design of the metal bunks was influenced by Tigerman's time in the Navy, when he learned about cramming a large number of people into a small space. Designed to be narrow (30 inches wide, as opposed to a standard 36 or 39 inches wide) to allow for broader aisles and more rows, the beds are made to be indestructible. Made from powder-coated steel tubing, the beds have a solid baked-enamel panel at pillow-level to offer a measure of privacy for residents. The rest of the panels are perforated to allow for a regular flow of fresh air. Speced to be 6-feet-3-inches-long to accommodate varied heights, the beds can be configured as a single bed, a bunk bed, or a set of two bunk beds connected to one another.